Sir Bernard Spilsbury had established his reputation even before the 1924 Eastbourne investigation which was to reach new heights in forensic medicine. Sir Bernard would later describe it as “my greatest case.” It was great because his task was to piece together a fantastically complicated jigsaw puzzle of more than a thousand pieces.

Spilsbury examined every room in the bungalow. In one of the bedrooms was a tenon saw. On the floor were articles of women’s clothing and a teacloth, all bloodstained.

In the dining-room fireplace were ashes, and these Spilsbury gathered up and placed in a container. It was in that dining-room that he found what in his own words were “the most gruesome remains I have ever seen.”

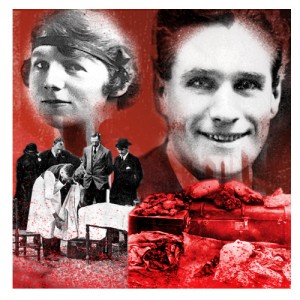

Utensils standing around suggested the use to which they had been put. In the middle of the room were a hat-box and trunk which had been moved from the bedroom. Both contained human remains.

From the hat-box Spilsbury lifted several articles of clothing with 37 sections of human remains. From the trunk he took four large pieces of a human body, all of which were covered with disinfectant powder. All the bones had been sawn across. On one shoulder he noted a recent bruise.

For three hours Spilsbury pieced the body together and found that everything fitted accurately.

Then he examined the ashes from the fires in the grates in the sitting-room and dining-room and those found in the dustpan in the scullery. Buried in them were between 900 and 1,000 pieces of bone. He matched them up – some formed part of the right shin, right thigh and left forearm.

With infinite patience he fitted these fragments together, and although they had been broken by the heat he could tell that they had been sawn through before being put in the fire…